BIOGRAPHY

Charles kocian Biography

summary

Charles Kocian, a former architect, entrepreneur, and now licensed sailboat captain, will continue writing his books from his sailboat — a project in development. From an early age, he was curious about exploring truth. That original fire never died. As a man who has truly discovered what it means to live as a rational animal, his personal mission is to promote reason around the world, as this poetry expresses:

…

Charles Kocian, sails the oceans,

Spreading reason around the world,

He is the right man,

At the right times,

In the right lands.

…

And those right lands,

Rise the right seeds,

For a new world,

The New Renaissance.

His books and game are tools of the King-Neo New Renaissance Movement, a self-educational system he created for eagles — eagles as the metaphor for people who dare to become heroes of themselves: optimal, rational animals. He sees them as the “diaspora of reason”.

Charles is passionate about science, sports, classical art, geopolitics and the beauty of nature. He designed a philosophical game accompanied by its book of answers. Along with his novel, these serve as instruments for the activists of the King-Neo New Renaissance Movement, whose primary mission is to follow the Champion’s Method — a 3-step method:

1

READ THE NOVEL

2

PLAY THE GAME

3

WRITE THEIR CHAMPION CONSTITUTION

BIOGRAPHY

(20 MIN READ)

London, England, Charles Kocian birth place.

Charles, still healthy and in good shape, was born in London, a very long time ago. His ancestors were Slavs and Celts from Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic. He has relatives there, as well as in Wales, England, other parts of Europe, and South America. Part of his family moved from northern Italy to Spain in the 16th century, and later to South America — settling in Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile. He enjoys history and world cultures, especially folklore.

Charles Kocian in the Pacific Ocean off the Chilean coast, Valparaíso, 2019.

His plan is to continue writing from his sailboat as soon as possible. Still a project in development, he intends to live on his sailboat year-round. In addition to writing, he plans to film his Philosophy Tour Videos in the Mediterranean Sea and Indonesia, as part of its marketing strategy.

He is a childless man who almost got marry three times. Once with Mónica, a beautiful friend of his younger sister; Sandra, another beautiful jewish woman; and Mariela, a model in Buenos Aires. But this love stories will be writen in Charles Biography he plans to write in the future, not here.

Although he once was a serious Christian, today he is a secular and an objective thinker, though he recognizes the power of the concept of God and respect traditions and religious beliefs.

A British citizen, he grew up in Chile and study in a British school learning English from a young age. He decided to write his books in English. He also speaks Spanish some French and Portuguese.

He believes that small governments, the gold standard, and strong family-based education are fundamental for a more rational world. He loves classical art, whose beauty he has discovered — and completely agrees with what his painter friend in Miami, Jaime Ferrer, once said: “Beauty is in nature’s order, not in people’s vanity.”

During the pandemic, he began studying programming and, with the help of his teacher, programmed his philosophical game. This came after working for eight years on his essay and novel. The essay, contains the answers to the philosophical questions of the game, 94 numbered questions; the novel, contains the characters who created the game and the essay.

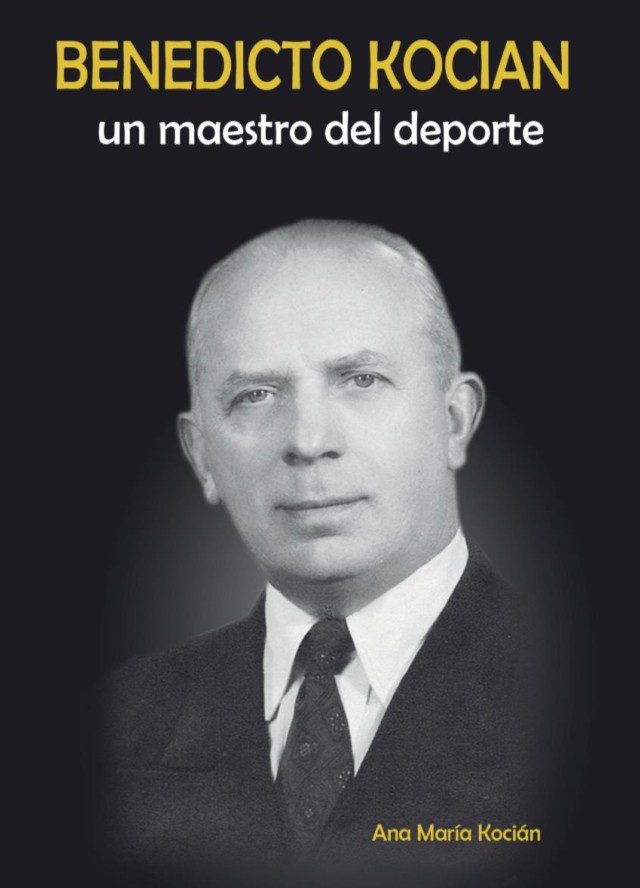

Going back to his early days, a couple of years after his birth, his family moved back from England to Santiago, Chile. At his grandfather’s Gymnastics Institute, VIDA SANA, he discovered a culture of sports and the well-being of the body and mind. His grandfather, Benedict Kocian, was an educator and the founder. He introduced volleyball and basketball to Chile. A Master Mason, he inspired him to do something big for humanity. He was an important, recognized, and award-winning citizen of Chile and the Czech Republic. Charles traveled from Buenos Aires to Tisnov in 2015 to receive the key to his grandfather’s hometown on behalf of the family, a recognition from the Czech government for his great work. He conserves the key as a family treasure.

Charles studied in a British school called Craighouse, one of the two best Bristish schools in the country of Chile.

He was a good student, and his classmates, to his surprise, awarded him the title of best friend. He only has gratitude for them. For the record, greetings to Alfonso, Daslav, Pablo, Max, Perini, Pedro, Rodrigo, Felipe, Francisco, Cristián, El Chulo, Carlitos, Eric, the Ricardos, Hugo, El Chino, Jose, Pataliu, the Patos, Maurice, the Oscars, the Daniels, Enrique, Lalo-Lalein and the two Marios, who sadly one of them died in 2024.

Indeed, Mario López Ibañez died that year. He was the doctor of Charles’ mother. They both were truly interested in science and philosophy. During the pandemic, Charles visited Mario’s house once a month, and they had great philosophical conversations in which both learned a lot. Charles recorded many of these conversations. He remembers when, still in school, he, El Chulo, and Mario would stay for hours discussing Plato and Aristotle with their philosophy teacher, Gaume Vidal, after class. It was the last class of the week, and all the other classmates would run home, but they stayed at school, sometimes until night.

One year before he graduated from school, in 1973, somebody baptized him, nobody knows exactly who and why, as Copernicus. Perhaps it was for his new ideas and attitude after comming back from a USA scholarship. Indeed, when he was 16 years old, through a Youth for Understanding scholarship, he stayed six months in a very wealthy baptist family in Camdem Arkansas. Becoming as one of his family members, he listen seriously his beautiful U.S. sister about the possibility of continuing living after death. If it was true it was worth, at least, to investigate it.

All his U.S. Camden baptist family communicated directly with God, they said. They prayed at the table with sincere attitude before start eating every meal. Charles felt uncomfortable, because he was interested in many things, but not God. But he prayed with them as a gesture of diplomacy and good manners, after all, they were the hosts and he was the guest. At that moment, his only experience with God was his First Communion, which he celebrated with all his classmates at age nine in Chile A Catholic priest had prepared them in his British school with a series of classes on the Bible. Charles was disgusted by the story of Original Sin in Genesis, in the Bible, when God condemns humanity because Adam and Eve ate an apple. God didn’t seem reasonable at all — He appeared irrational and violent. That frightened him. But he was also mad about this violent God — a kind of psychopathic, irrational supernatural entity. Afraid of more violence from the tyrant God towards him, he hid his rage within himself, in his subconscious. He recognized it later in his adult life. From there, he drew many conclusions and learned many lessons. But at 9 years old, he was both mad and afraid of the supernatural tyrant. Despite his young age and limited information, he was sure it was unfair to be cast out of Paradise without committing the crime.

At sixteen, before he was baptized in the Baptist church, Charles considered God merely a social moral attitude, but never prayed seriously as is He really existed. His great mistake was to ask with intellectual honestly: what if the afterlife is not just a saying but a real fact? Would he lose the opportunity to continue living after death if it was an objective truth? What if is a question that can be a very dangerous question, and this case it was, as the gate to enter the laberynth of philosophy.

Regardless, he decided to undertake a serious, methodical, and rational investigation of God. The best way to start was by reading the entire Bible. His sister advised him to begin with the New Testament. He liked the Gospels, but there were some issues with Jesus that didn’t make sense. Would the story have spread as it did without the miracles? Would it have spread without Constantine’s conversion to Christianity to rule a decadent Roman Empire? But the greatest absurdity of the New Testament was the Apocalypse: God appeared as a violent ruler who demanded the rejection of thought, logic, and the scientific method. In fact, Jesus demanded faith as a condition for being loved and not being sent to hell.

He read the Bible with serious intellectual honesty, trying to find meaning and cause-effect relations. His baptist family invited him to be baptized an converted, and he accepted. He was baptized and converted in the Camden Baptist Church in 1973. When he returned to Chile, his classmates, real family, and friends were shocked. They almost didn’t recognize him. His change was like a Kantian Copernican revolution, not only for himself, but for everyone around him. This is most likely the reason why some of his classmates nicknamed him Copernicus.

This was not the end of the story, but the begining of his philosophical journey. Indeed, because a lot of things didn’t make sense in the New Testament, he decided to read the Old. Why? To understand the cause of the apparent nonsense of the New. He believed that the Old and the New should follow a relation of cause and effect, as in chemistry, logic, physics, mathematics, and history.

He read the Old Testament, but didn’t find a hidden cause that could explain the nonsense of the New. The result was even worse. Nothing made sense. The only way out seemed to be to stop thinking, to abandon logic, and to let himself be guided by faith and emotion. But that didn’t convince him at all. He knew he was in trouble — trapped in a labyrinth.

It can be said that this was the beginning of his philosophical journey. Juan José Diez — now a lawyer, academic educator, and philosopher — was his first philosophical friend when he was 18 years old. As teenagers, they became well-versed in the book I’m OK, You’re OK, which introduced them to transactional analysis. Charles’s inquiry was wide-ranging, exploring Freud, Jung, Gestalt, Yoga, Zen Buddhism, and more. The journey was tough and bitter. But after a long struggle, we can say that today he finally found his way out of the labyrinth. Now the fruit is rich and sweet, and he shares it with others through his books.

There are too many details to recount here; the rest will be told in the memoirs Charles will write in the future.

An outstanding athlete, he was selected for the school rugby team, competing in championships with other British school teams, including in Buenos Aires. He also played football, tennis and joined the swimming, volleyball, roller hockey and athletics teams at the Italian Stadium, located next to his father’s house. In his youth, he also went snow skiing every winter, and in the summers, he did water skiing and windsurfing.

His father’s name was Hebert Torrico. Son of Eloy, who owned a school in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Hebert was a heart surgeon specialist and educator, who studied medicine at the University of Chile, and make two postgraduates degrees, one year in Detroit and two years in London, where Charles was born. He also had a weekly medical podcast for the overseas in the BBC. He remembers him with gratitude as a great father, shameless, with a very funny sarcastic humour. He was a generous, intelligent and courageous man. Hebert married his mother, Ana María Kocian, an interior designer and educator who also studied at the same university — a sweet, rational very healthy woman. His sister Ximena married another architect, Coke, and they had Matías and Pascal.

As a young boy, he discovered sailing with a friend’s family who owned a sailboat. Later in life, he practiced parachuting, training with the Chilean Army Commandos and completing 117 free jumps with his own parachute. He also practiced judo, box, aikido, karate, and krav maga. Now, he only does calisthenics. But not everything was sports, as he also studied music and piano, and learned to play the guitar on his own. He spend a lot of money building its own home musical professional studio, with an electric piano and other instruments, and all the necessary hardware and software to create and mix music. He loved to compose music, with its guitar or the electric piano, which was a synthesizer with more than a thousand instruments that sounded just like the originals. He took particular musical classes for four years and produced a CD of instrumental music.

After school he studied three careers at Universidad de Chile, one of the oldest and most prestigious of all, founded by Andrés Bello in 1842, who was one of the teachers of Simón Bolívar.

First, he studied dentistry with the intention of transferring to medicine, taking classes in common with medical students at the School of Medicine called JJ Aguirre. Second, he studied two years of engineering (forest engineering in the Antumapu Campus). Third, he spent six years studying architecture and urbanism, eventually becoming an architect. During the latter, he became friends with Pablo, Pepe, and Fernando. They know who they are, but don’t worry — we’re not going to overdo it by giving more names. His thesis project to become an architect, was about a spiritual retreat center for Hermetic philosophy, and he passed with distinction.

Apart from founding his own architecture and construction company, he first worked at some of the best architecture firms, such as Alemparte Barreda & Associate Architects, Carlos Alberto Cruz & Associate Architects, and Alberto Montealegre Beach & Associate Architects. He also was the Director of the Extension and Improvement Center of the College of Architects of Chile. Later, he did a Chilean-Spain MBA in real estate development and a post-graduate degree in international commerce. Although he has created many different kinds of entrepreneurial ventures, as an architect, he has worked in the construction and real estate industries in Santiago, Montevideo, and Miami. In the process, inspired by Robert Kiyosaki’s books, his board game, and his friend Juan, he achieved financial freedom.

But most importantly, alongside his professional life, he studied psychology and philosophy on his own. He read many books and participated in many groups.

Inspired by Simón Bolívar, he founded Nuevandes, his own cultural organization aimed at unifying South America through art. At the time, it was a small group. There was an official inauguration and cocktail attended by around forty people. The organization had a board of directors who held weekly meetings, keeping records in a minutes book. Shortly after, due to internal rivalries, he decided to put the organization on hold.

He also spent three decades at the Hermetic Philosophic Institute. In reality, it is an inappropriate name, as it is more mystical and pseudoscientific than philosophical. Some detractors even say it is a sect. Charles reserves his opinion on this, but encourages anyone to study the facts, in light of sect specialists, to arrive at their own conclusion.

Always driven by the desire to do something significant to improve humanity, he became an outstanding student and leader, reaching the highest degrees and learning many important practical lessons, especially self-discipline.

For more than two decades, he was in the GAM group, the organization’s highest authority, but outside the organizational chart, the real power behind the power, “la crème de la crème”, as Anatole, a funny corageous Russian member use to say. To integrate it and stay in, was tough, very tough. You needed a personal invitation of Darío Salas Sommer, the founder of the Institute. Charles became his architect. Among many projects, he led the Kosmos Project, a large initiative featuring expansive spaces for educational events on a 200-acre property in Casablanca, near Santiago. The project was designed to serve as the international headquarters for the organization. Within the same inner circle GAM, Salas invited him to join a non-political educational movement to unify South America, based on Simón Bolívar’s vision. Charles remembers his time in the Institute with gratitude and pride. He had a very good time and made very good friends, like Carlos, the Casanova of Trauco; Jaime, the dentist colonel; Daniel, the lawyer; Domingo, the surgeon; Nicomédes, the Venezuelan diplomatic who built a sailboat in Arrayán and Charles helped him; Polo, the industrialist; Antonio, the psychologist; Rubén, the pilot and owner of three planes; Jorge, the real estate manager; Constantino, the chemist; Anatole, the shameless Russian veterinarian; Luis, the wealthy Spanish entrepreneur with a golden heart and a 46-foot sailboat, whom he used to sail with; Manuel, the millionare of the fruit industry; Hernán, the manager of the organization; Adolfo, the black belt ninya turtle; and Alberto, the Xerox salesman. He almost marry Sandra, a jewish woman in the Institute of Santiago, and Mariela, a beautiful model in the Institute of Buenos Aires, when Charles lived there for four years. In Buenos Aires, he also became good friend with Mario, Daniel and Carlos. On both sides of the Andes Mountains, people know who they are, and he has only words of gratitude for them, despite their mistakes. This is for the record, but we will not mention any more names except Cow friend, the only person Charles invited to the Institute.

Unfortunately — very unfortunately — because he left behind many dear friends, he later discovered that Hermeticism was wrong. Indeed, the book The Kybalion, with its seven Hermetic principles on which Hermeticism is based, was pseudoscientific — rooted in Plato’s duplication of the material world. Realizing that mystical premises and Plato’s ontology were wrong was a philosophical disaster. But as Nietzsche said, “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” So, although its old premises were dead, new objective ones were born. It can be said that, in the Phoenix fire, the old God died; the objective ONE arose, verified. Let’s dive a little bit here because it is fundamental imporant.

For the first time in years, he deeply questioned the seven Hermetic principles, written in The Kybalion, on which the mystical part of the Institute’s philosophy was based. The book was originally published in 1908 by unnamed authors calling themselves the “Three Initiates” and was issued by the Yogi Publication Society in Chicago. Its underlying philosophy was based on Plato’s theory of a dual world — an invisible world of Forms creating the material one — an erroneous concept that serves as the foundation for many religions, mystic groups, and ideologies. By the way, how many cultural premises are Trojan Horses, downloaded in our childhood without any critical thinking? Are people trapped in them? Does a child absorb or discover his cultural premises? Does he passively accept them, or use critical thinking? The latter is the first question of the philosophical game.

Charles discovered that God, as consciousness preceding existence, could not have created the universe. If consciousness is perception, how could any consciousness be aware of something if there is no signal emitter and no signal receptor? Can something be perceived if there is nothing material to be perceived — or no sensory organs to perceive it with?

If one thinks about it carefully, one will realize that no —it cannot. Consciousness cannot exist prior to existence; sensory perception cannot occur without sensory organs and something material to perceive. To accept the primacy of consciousness over existence is to destroy our primary tool of survival: reason. It is both absurd and dangerous — and a deep cause of psychological insecurity, lack of self-confidence, and diminished self-esteem, regardless of social status.

As one of the characters in the novel says: “You cannot kick a penalty without a ball.” You cannot even see it if you don’t have eyes — let alone if there is neither ball nor eyes.

If God is conceived as consciousness before existence, then it is impossible. But God exists, religions exist, and they have played a kind of primitive yet positive role in society — a role that must be acknowledged and respected. So, if God exists, it must exist in this kind of respectful cultural and imaginative form, but not in a scientific, objective, ontological, or metaphysical one.

These reflections led him to stop believing in God as a consciousness preceding existence. He weighed the possible consequences of being wrong, and the margin of error seemed low — so he took the risk. He accepted that he would live a single life on this Earth, with no expectation of an afterlife.

But if he turned out to be mistaken, and after death found himself standing before God to be judged, he would say:

“If You truly exist and possess omnipotent power and love, then forgive my error. I acted in good faith, using — to the best of my ability — the highest faculty you gave to man: reason. But if you still wish to send me to Hell, as the Inquisition did with Galileo, then I say to You — and to whoever wrote You into existence as a terrifying tool for social control — to all of you: fuck off. Erase me from your database.”

Without the God premise, there was no divine spark. What sense did Hermeticism make if it began with the assumption that man possesses a divine spark? After all, the entire spiritual work of the Institute revolved around nurturing that spark. How? By understanding the essence of concepts — that is, by delving into the meaning of words. But how could one nurture a spark one didn’t possess? Again, what sense did it make to remain in the Hermetic Institute, knowing one lacked it? It made even less sense once he discovered that — contrary to the claims of both Hermeticism and Aristotle — the essence of concepts was not metaphysical but epistemological.

An epistemological essence has no substance because it is a method, a psychological action, not an entity. So, even if a divine spark existed metaphysically as an entity, the epistemological essence of a concept could not nourish it, because it is not metaphysical but epistemological — that is, not an entity, but an action. Epistemology concerns psychological actions and methods; metaphysics concerns entities. Entities are nourished by consuming other entities; they cannot nourish themselves by consuming actions.

Although Charles’ discoveries remain, and he still knows that God might be a cultural cognitive error or a tool used by psychopath rulers, he is now exploring the concept of God from a completely new perspective. He hypothesizes that the concept of God, meaning the real or objective God, could be the highest human abstraction, formed through unconscious inductive-mathematical reasoning, in the same way all concepts are formed — from the lower abstraction of an apple to the highest abstraction, the concept of God.

He is currently writing a book on this idea, titled MASI IS GOD: The Inductive Math Formula for the Concept of God. Indeed, we know that the mathematical beauty of the universe exists, as Carl Sagan illustrated — but so does man’s mathematical-inductive faculty in concept formation. The true God is the mathematical integration of both. Charles named it MASI and wrote its mathematical formula. We will have to wait the book to read more. Now let’s return to the biography.

Recovered from that philosophical catastrophe — when evidence shattered Platonic pseudoscience— he immersed himself in the objective epistemology presented in Ayn Rand’s Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology. He was shocked to learn that the essence of concepts was not metaphysical but epistemological. While he agrees with Rand on the fundamentals of reason and concept formation, he disagrees with her on the practical implementation of capitalist theory —because in the real world, there is no objective justice. Justice is not anchored to reason and facts, as it should be; it is corrupt in many places, for many reasons. There is no objective justice in local affairs, nor in international relations, nor in the global financial system. The latter is not based on metallic gold but on a sophisticated deceit in which major banks and central banks are complicit.

Charles doesn’t belong to any organization, but he has studied Ayn Rand’s works deeply and has only words of profound gratitude for her — especially for her unique contribution to epistemology, particularly her assertion that concepts are the algebra of cognition. That is truly profound. He also has great gratitude for Leonard Peikoff, with whom he once had an email exchange related to the theme of envy, a well-known subject to Charles after studying Melanie Klein’s book Envy and Gratitude for five years. He thinks Peikoff’s books on Objectivism and The DIM Hypothesis are superb. He is also grateful to Harry Binswanger, who delved deeply into concept formation, writing books like How We Know: Epistemology on an Objectivist Foundation and many others. He is also grateful to the psychologist Nathaniel Branden, who co-authored The Virtue of Selfishness with Ayn Rand. He played a key role in the early promotion of the philosophy of Objectivism and became a specialist on self-esteem, writing book like: The Psychology of Self-Esteem; The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem; How to Raise Your Self-Esteem and many others. Charles has not only read all the books of this authors, he has study them for years and has only gratitude to all of their authors.

As mentioned, although Charles is not an active member of any organization, he knows people like María Marty, Tsal Tsany, Yaron Brook, and others from the Ayn Rand Institute ARI whom he met and shared ideas in Buenos Aires in Objectivist events.

Today, we can say that, due to his journey, Charles has achieved a deep understanding of philosophy, grounded in Aristotle’s and Objectivist epistemological premises. But his inquiry has not ended — it is just beginning. He wrote a personal Champion Constitution for himself and lives by it every day. The philosophical game he created starts just like that: players crafting their own Champion Constitutions. Indeed, his works are part of his own self-growth process, including the King-Neo New Renaissance Movement. This movement does not pretend to implant a desire in people who don’t resonate with reason as man’s highest value. It is simply calling those who already have that desire and want to work with a method to become the best versions of themselves — to live as heroes.

There are many kind of heroes that has inspired Charles, but the ones who have inspired him most are John Galt and Achilles in fiction; in real life, his grandfather, Confucius, Aristotle, and Simón Bolívar. There are many others, like Einstein, Newton, Mozart, Galileo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo. All of them were advocates of freedom through inquiry and education.

So, Charles is already committed to an educational feat meant for eagles — the metaphor for those fiercely devoted to reason and determined to rise high enough to see the big picture. This movement is only for Everestians, another metaphor for those who dare to climb their own Mount Everest: the best version of themselves.

This was a brief, perhaps not so brief, story of Charles Kocian. The important details are there.

For the record, in 2019, he changed his first and last names for marketing reasons. His London birth certificate reads John Charles Philip Torrico. In Chile, his first names were translated. It was a very long name, not easy to remember internationally. So he chose his first name Charles and his mother’s last name. Charles Kocian is shorter and a better name for an international writer.

His mother Ana María, by the way, wrote a book of her father called Benedict Kocian, A Master of Sports. Zora Kocian, Charles’s niece who lives in Wales, UK, translated it from Spanish to Czech. Zuzana Kocian, other Charles relative who lives in Iceland, wrote a book of the Kocian family. In the decade of 1990, Charles and her mother were part of the legal founder members of the Czech-Chilean Circle, where his mother remained twenty years as President. Its cultural activities are made in close relation with the Czech Embassy in Santiago of Chile.

Charles Kocian’s grandfather on the cover of the book.

Many things were left out, but the most important is that Charles Kocian is a man who chose reason as his highest value. From here, the best is yet to come.

Copyright © 2025 by Charles Kocian. All rights reserved.